Interview with Rut Blees Luxemburg, artist

Conducted by: Tom McCarthy (General Secretary, INS)

Venue: Office of Anti-Matter, Austrian Cultural Institute, London

Date: 27/03/01

Present: Tom McCarthy, Rut Blees Luxemburg, Corin Sworn, Thom Osborn

Rut Blees Luxemburg: I've brought some new work - which you know.

Tom McCarthy: Oh yes: that's the work from Paris. I haven't seen this, though.

RBL: It's called 'The Dandy'.

TMcC: The Dandy: the Flâneur.

RBL: No, 'The Dandy', not 'The Flâneur'.

TMcC: Why 'The Dandy' and not 'The Flâneur'?

RBL: I'm not interested in the flâneur. I reject the flâneur.

TMcC: Oh really? But the dandy is the flâneur without the art.

RBL: No, I think they're two separate entities. Do you like the photo?

TMcC: Yes - but what am I actually looking at?

RBL: You can't work it out?

TMcC: It's a marble wall above a ventilation grid in a bank or something.

RBL: An office for medical analysis.

TMcC: So that's the skeinwork on the marble?

RBL: Yes, and it forms this horrific face, the face of the dandy. It looks like it's underwater.

TMcC: It's beautiful. And the tree roots in this other one form…

RBL: Veins, yes, like an old woman's.

TMcC: Varicose veins. Those are roots of a tree, are they?

RBL: Yes. And you know how they then change the ground…

TMcC: You get that fluid look in a lot of your pictures: becoming fluid. What have you called this one?

RBL: I'm not sure yet, but it will be on the notion of the journey home.

TMcC: You seem in your work to have developed a way of accessing, mapping and, in a more vague although equally striking sense, of occupying or persisting in spaces that the rest of us have trouble even noticing, let alone making visible. How do you find these spaces?

RBL: My methodology is based on walking. Walking has this effect on the wanderer of creating a rhythm and within that rhythmic walking your mind, at least in my experience, becomes more free, and in that special heightened awareness you then are able to notice places. It was Nietzsche who said: 'Nur die ergangenen Gedanken sind 'worthwhile', so to speak.' Only the thoughts formed during walking are worthwhile. That's something I find quite important for my work.

TMcC: Why do you take your photos at night?

RBL: Again it goes back to finding a space. The night is a time where the everyday recedes, and this creates this heightened awareness which I'm after. In German we say someone is 'Geistig umnachtet', which means their spirit is covered by the night. It's used to explain madness, but at the same time for me the idea of the spirit covered by night offers other possibilities of connection.

TMcC: Do you go alone?

RBL: Sometimes I go alone and sometimes I have an assistant. But it's not a question of aloneness which is really essential. I'm always asked this question 'Do you do it alone?', as though this solitary walking would be somehow more worthy, but I don't think so. I only go with very special people who I have a strong relationship to, so we get into this mood together.

TMcC: Do you plan your routes in advance, or do you just see where the mood takes you?

RBL: I wander, but I go to places which seem attractive to me. So I wouldn't go to Oxford Street, but I would go to the river.

TMcC: Your first major collection was called London: a Modern Project. As with all of your work, the title is very significant, especially that word 'modern'. You've written and talked in the past in interviews about the connection between modernity and vision, types of vision. So how would you say modernist visual aspirations and achievements vary from, say, those of their Romantic predecessors - and how important is the advent of your craft, photography, in this?

RBL: I can only explain this in relation to that body of work I did. The term 'modern' was as much ironic as it was real, because if you look at contemporary London there are so many paradoxical situations that emerge through that collision between different time zones. But there's a strong modernist architectural heritage within the city. I'm trying to see if I can penetrate that, or to see if there's space for not just penetrating but also detonating those conceits, because one is strongly aware of how the built city actually affects the subject, affects us. Is there then space to manoeuvre within this manifestation of modernity? Now, the relationship between modernity and photography I don't investigate as such. I take photography as the tool, and it's not even so much a modernist tool. It goes back to the Victorian age, when photography was invented simultaneously in France and England.

TMcC: Then that word 'project', and modernism as a project failed or realised… Maybe modernism can only fail as a project.

RBL: Or maybe, as Habermas says, it's unfinished.

TMcC: Yes, 'project' has the sense of something still under construction. As you point out, photography goes back to the Victorian era. And modernism, too, has its roots in Romanticism, but in a decaying Romanticism. You get Yeats declaring that 'The woods of Arcady are dead', and in Joyce's Ulysses there's that decrepit milkwoman with missing teeth, this pastoral idyll fallen into decline. I know that you've got very strong literary influences, and take lots of your inspiration from poets. In the past I've seen you hold up the German Romantic poet Goethe's character Faust as a modern archetype: the archetype of the subject with controlling vision. This is particularly interesting in the context of London: a Modern Project, because lots of those photos are about control: controlled movement in the ones of the traffic, controlled leisure in that one Corporate Leisure that shows a caged-in, is it a tennis court?

RBL: It's a tennis court.

Corporate Leisure, 1997

Courtesy Laurent Delaye Gallery, London

TMcC: So it's about control, but at the same time it's about losing control, especially in that fantastic photo Vertiginous Exhilaration,, where you're on the twelfth floor and the image shoots down towards the car park. It almost invites the viewer to deliver themselves over, to jump. Is the tension between control and surrender deliberately set up?

RBL: Yes. And that image is very much influenced by an image by Caspar David Friedrich, Kreidefelsen auf Rügen. It's a group of three people sitting on top of this white chalk cliff, and one of them dares to look downwards. Do you know it?

TMcC: I don't think I do.

RBL: And another character looks across the horizon. He's in a typical Friedrich pose of contemplation and self control and ability to recognise the supposedly sublime. But I'm much more fascinated by the character who's daring to look down, and who is so close to slipping and falling. And with Vertiginous Exhilaration I also wanted to see what happens when you direct the camera downwards, when it's no longer taking in the panoramic beauties of the urban sprawl but rather contemplating plummeting onto a hard surface. But in this photograph you go backwards and forwards.

Vertiginous Exhilaration, 1995

Courtesy Laurent Delaye Gallery, London

TMcC: It's like a spring: the same pattern repeats as each floor goes down.

RBL: So it spins you back. It's not really a suicidal, diminishing view; it's one of tension and being held in space. I'll give you a Deleuze quote about this, which he calls 'limitless vertigo'. He says: 'Great dimensions, depths and distances which the observer cannot dominate. The privileged point of view has no more existence than does the object held in common by all points of view. There is no possible hierarchy.' So that goes against a Faustian view of control, domination, building a city.

TMcC: If we stick with this figure of Faust for a moment: he, too, for all his proactive mastery of craft, is in a vital sense passive. He, too, gives himself up to Mephistopheles, delivers himself over to this other being who has eternal mastery over him. Now, your most recent collection, Liebeslied, 'Love Song', is characterised by a similar passivity. All of the action and acceleration of London: a Modern Project has given over to stasis, to a sense of things slowing down, immense slowness.

RBL: Slowness, sure, but I wouldn't say stasis. And I wouldn't quite agree with Faust being a passive character. If you see Mephistopheles as a separate entity from Faust then maybe, but I see them as one person: Mephistopheles is the other side of Faust. And I think that what you perceive as slowness is for me getting away from the geworfen, the 'thrown' of the Modern Project to an immersion. So it's a slowing down of the speed, but that doesn't make it static. And slowness I think is, paradoxically, potentially faster.

TMcC: How so?

RBL: In that the slower you go the more you perceive.

TMcC: So it opens up speeds of perception?

RBL: Yes, or different intensities of perception.

TMcC: Was the technique you used to take those photographs different from in London: a Modern Project?

RBL: No, it was the same.

TMcC: You have very long exposure times.

RBL: In both works.

TMcC: How long?

RBL: It varies between ten, eighteen, twenty minutes sometimes.

TMcC: You've said of those photos that they're not constructed: they 'emerge' - that's the word you use.

RBL: Yes. They're absolutely not constructed. I don't meddle with the scenarios I find. They're very much based in reality. But though they have a quality of otherworldliness about them they are here, and it's quite important for me to be out there in the real world and deal with what is surrounding us. So it's not fictions which I create in the studio or around me; it's finding and concentrating on what is already there.

TMcC: With this matter of the long exposure: I suppose it's possible that there are things in there which we don't actually see. If a cat passes by, or a human even, it wouldn't register.

RBL: Yes. They don't leave any trace.

TMcC: Did that actually happen during the shooting of them?

RBL: It always happens. The beauty of this long exposure is that chance can enter the image. There's space for contingency. Although it's very controlled in the set-up, once it's all open, once the camera's open, all sorts of things can take place which are beyond my control.

TMcC: It seems to me that a term I've heard you use before, this German term 'Abgrund', is relevant here. What do you mean when you use it? It means 'background', doesn't it?

RBL: No, Abgrund is more 'abyss'. It comes from 'founding': founding ground. Grunden is to create, to found something; and the Abgrund is for me these very special places within our city where something can still be sensed, something can still be traced. For example, in my work Das Offene Schauen I photographed such an Abgrund. It's a forgotten car park filled with puddles, and in this place, as Hölderlin thought, you can still trace the absence of the gods. They've left long ago, but somehow they can still be traced in these Abgrunde. 'Traces of the presence of the gods.' The Abgrund is an all-remembering, an alles merkende space where you can still hear the lost song.

TMcC: So it's a space of hypermnesia, the opposite of amnesia…

RBL: Yes, it's a place of a certain kind of memory. It's time-travel space.

TMcC: I like this conjunction, this architectural metaphor, foundation, that becomes a mnemonic one and also a metaphysical one. But a distinguishing feature of all of your work is the total absence of all human figures.

RBL: Yes, I don't photograph people. But I photograph their absence, so to speak.

TMcC: And you strongly imply people everywhere. Like in this one Enges Bretterhaus, 'Narrow Stage', you show the worker's cabin, and his chair and even his cup of coffee. And in Nach Innen, 'In Deeper', you show the footsteps by the river. They're disappearing into the river and also coming back out. Did you find those or did you make them?

RBL: Is it important? I wonder, I don't know if it's important.

TMcC: I think it's important. You're free not to answer the question, of course…

RBL: No, I can answer this. The footsteps are of my assistant, going down and coming back.

TMcC: It's very important that they come back. It completely changes the meaning: disappearance and reappearance.

RBL: Yes, but only when you look very closely do you realise that.

TMcC: And you could have chosen to have your assistant step back via the footprints he'd already made. If it only went one way it would imply suicide, Paul Celan's suicide in the river maybe.

RBL: Yes - but I don't photograph people precisely because I don't want them to occupy the space. I want it to be possible for the viewer to make that mental leap of inhabiting the spaces themselves. And I think that if I'd shown the person walking to the river and coming back it would prohibit poetic readings.

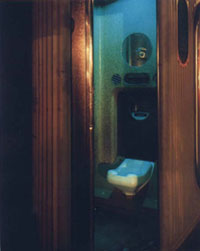

TMcC: The photograph in Liebeslied that most implies the presence of a character, to the extent of actually naming him in its title, is Orpheus's Nachtspaziergang, 'Orpheus' Nocturnal

Walk'. You see a toilet with a blue light in it, and the door is invitingly open, as though either someone had disappeared in it or it's inviting the viewer in. That one raises an essential question for me that I think you could extend to all of your photos, which is: are you equating Orpheus with the character who's taken the walk and disappeared, and we come afterwards and see where he's disappeared? Or is it equating Orpheus with the viewer - that the viewer is Orpheus being invited to enter the space? In that sense it applies to all the photographs: who is the subject of these photos? Whose Liebeslied are they?

RBL: In one sense it's the Liebeslied of the absent poet who goes through all the works. In another way, of course, it's my own Liebeslied: it's my Liebeslied to the city, and it's my love song to my lover, and it's also the viewer's potential love song. So it's not as clear-cut as 'Here we have a character'. No: the character has multiple personalities and can be inhabited by many people.

TMcC: Orpheus was himself a lover, of course…

RBL: Yes, and a toilet, especially this kind of public toilet, is a place of meeting the other, looking for one kind of love. This work in particular was very much inspired by Cocteau's Orphée: here you could go through the mirror which is above the toilet, but you can also vanish inside the toilet bowl. Or come out again through the door.

Orpheus' Nachtspaziergang / Orpheus' Nocturnal Walk, 1998

Courtesy Laurent Delaye Gallery, London

TMcC: The love theme of the collection's title is replicated in the title of another image, 'Versuch der Betörung', 'An Attempt at Seduction'. This one shows the shadow of a skein of trees' twigs reflected on a wall. But I wonder: do you see the spaces that you're photographing as essentially erotic? What type of seduction do you have in mind?

RBL: Well, if the city is the place of meeting the other then it's also the place of potential erotic encounters: the poet, or the walker who uses the city as a place for cruising and for finding love. But it's absolutely not the walking of the flâneur, who looks for quick kicks and a fix of - it's not that kind of eroticism that I want to find within the city. It's love instead of sex.

TMcC: Beside the figure of Orpheus I felt that there was something very Ovidian about many of the photographs in Liebeslied, which was the fact that all of the bodies, all of the surfaces, matter itself seems to be in a state of transformation. Hard edges turning soft and running, trickling, becoming puddles in which other surfaces are reproduced and reflected and also rendered liquid. In the poetry of Rilke, which your photos very strongly bring to my mind, this dissolving, this Entlösung, is not just a physical but also a metaphysical event, a transcendental one. Do you see it the same way in regard to your work?

RBL: Yes. And I want to emphasise the liquid. I see it like the stains on the street. All those puddles are like incontinences of the city.

TMcC: Some of them look like urine or blood. Not specifically, but in the sense of something that's leaked.

RBL: Yes, and this liquid is in opposition to the 'Blut und Boden', the 'Blood and Earth' ideology of Germany. And in my desire to make it liquid I want to emphasise the possibility of transformation. And your feeling at home, your Heimlichsein, is no longer based on concrete earth, but is now able to understand the importance of the fluid and the liquid.

TMcC: I'm glad you brought up that heimlichsein trope, because one of those photos, the one of the ruined house in which half the place has fallen away but you can still see the groundplan of other rooms through the brickwork: it's a very beautiful, very eerie photo. But in English it's called Affliction, whereas in German it's called Heimsuchung, 'looking for a home, homesickness'. Why the inconsistency in the title?

RBL: But it's absolutely not inconsistent. It's actually a slip in translation which is for me very fascinating when you use both languages, German and English. So Heimsuchung has within it the search for the home; but at the same time it means 'damnation', 'affliction'. It's the worse that can befall you. Why that meaning is within the search for the home is mysterious, but it's very very powerful. This search for the home is something that's very important in the Liebeslied, because the home haunts all our thoughts and memories. And that's why I want to liquefy this search for the home and show that it's not based in this structure of the actual home but that it's possible to find a home even in the river.

Heimsuchung / Affliction, 2000

Courtesy Laurent Delaye Gallery, London

TMcC: The urban spaces in Liebeslied are all broken spaces, abandoned spaces, spaces of decay. You see graffitid staircases, overgrown wasteland, the ruined house we just mentioned. If London: a Modern Project set itself among the Utopian visions of modernity, would it be fair to say that Liebeslied takes place much later, in a different epoch, one that comes after the collapse of all visions, of all projects?

RBL: Well, in a way there's a collision of different time zones. You could say Liebeslied is based in some apocalyptic future, but at the same time it precedes A Modern Project. It goes back to a much earlier, maybe even pagan age.

TMcC: What are you working on now?

RBL: I'm working on Paris. The new work is based on horror. And it's also very much influenced by Schönberg's Pierrot Lunaire, which was a - not an opera, but a text-based piece. And in it the main character, Pierrot Lunaire, is suffering from insomnia, and he has one of those nights of being utterly unable to sleep, and he's haunted by all these obsessions, blasphemies and fears. It's for me a very powerful state of mind, and this night, this horrible night, is one which I find quite timely now, especially in Paris, which is such an overmythologised city. So by connecting with horror I was able to uncover another layer. And I'm now creating almost a human body out of different components. So far I've got the hand, the legs and the face. I use Schönberg's Pierrot Lunaire to find the different stages of this cycle of one night. So it goes from unwieldy obsessions into relief, finally - and this relief comes through a strong sense of memory.

TMcC: So the legs would be those varicose veins…

RBL: Caused by the roots of the tree growing underneath. Something we haven't talked about is nature within the Liebeslied.

TMcC: Nature's much more prominent in those. I think it's completely absent in London: a Modern Project. I can't think of a single natural motif in there.

RBL: Neither can I. But in Liebeslied I found myself drawn to spaces where nature somehow still managed to exist within the city, and where it also controlled my works through its cycle. So I had to wait for example with Nach Innen for the tide to go down to reveal the steps, which happens twice a day. And I had to wait for it to stop raining, so that the puddles' surface was clear and not broken, to reveal what was reflected in them. So nature dictated a different kind of working rhythm to me, which I find really important: to connect for myself with nature, but in whatever perverse way it still existed within the city.

TMcC: You're from nature: you grew up in the wilds of Rheinland…

RBL: I grew up in the beautiful countryside of the Moselle. So maybe that relates to the idea of the search for the heim. So in the new work I'm doing in Paris, in the final sequence of this terrifying night, the memory of home, the smell of the old trees leads this afflicted character to find some peace.

TMcC: How is that manifested photographically?

RBL: In that the trees have created these monstrous yet very beautiful veins underneath the tarmac, which lead you…

TMcC: There's a strong sense of direction: lines…

RBL: Yes. And narrative direction: it was helpful to me to have these stages of one night in the new work. In Liebeslied, by contrast, the images can be ordered in any way, shuffled like a pack of cards.

TMcC: Tell me about your collaboration with the philosopher Alexander García Düttmann. Did he choose the title My Suicides for his text accompanying Liebeslied?

RBL: Yes, he did. And it surprised me, because suicide was actually the last thing on my mind when I did the Love Song.

TMcC: But the way he understands suicide is as quite an amorous configuration. In that one 'The Wire' he says something like: 'The suicide is the one who rejoins himself at the very limit of himself, where he becomes other.' It's not depressing: it's about love.

RBL: Yes, certainly.

TMcC: And did you discuss what he'd write?

RBL: Well, I knew that he also came from a certain German tradition of engaging with love through poetry and through German music, so he seemed to me the right character to engage with it. But then he took it on a very personal level of his own love song. So his 'suicide' is his love song to his absent lover. And I'm very happy with this reading. I'm happy that he took it on so personally and took it so far.

TMcC: I understand you're working on an opera.

RBL: Yes. We're at the very early stages of making the Love Song into a musical piece. We've got a young composer called Paul Clarke who's working on the music, and we're thinking of having three sopranos, three female singers, who'll play the writer, the photographer and the lover.

TMcC: Why all female?

RBL: Well, it's the choice of the composer. He likes female voices. And the question of gender is one which it's important to play with and to explode. That's something Alexander García Düttmann does very interestingly in the text, where the 'you' and the 'he' and the 'she' always change around.

TMcC: It's an indeterminate triangle. As soon as you think you've got it, who's male and who's female, who's in love with whom, it shifts. It's rather like Shakespeare's sonnets. But in your opera the photographs will be the set?

RBL: Yes, and they'll change. And the singers will move among them, and if we work it out then maybe the audience will also be able to walk among the images and the singers.

TMcC: So the singers won't become protagonists within the photos; you still want to maintain the absence of direct representation of people.

RBL: Yes. The images will be a stage set. They'll be almost like the choir within the scenario. They'll inhabit their own space.

TMcC: I wonder if Heidegger and his idea of Holzwege, and of travelling through, has any bearing on your work? He's all about movement and projection, being geworfen, being cast out, cast into, and he also thought of subjectivity as unrolling across time, across being-in-time. And then the Holzwege, these paths. I imagine someone could do an interesting Heideggerian reading of your work.

RBL: Yes, but I wanted to take it in another direction by emphasising the fluid. The Holzwege, of course, are somewhere in the Schwarzwald, and it has quaint yet suspicious connotations. I'm much more interested when the Wege become liquid, when it becomes much more about the movement, say, of the river.

TMcC: Is there any particular poet or thinker that you look to when you think of fluidity?

RBL: Yes, I think about Hölderlin. He wrote a lot about the river, this wonderful metaphor of crossing boundaries and nations, and also being able to be at home within movement. That's something I'm trying to understand with my work. I call this image of the river Die Ziehende Tiefe -

TMcC: 'The Pulling Deep'?

RBL: Ziehen has this sense of pulling, but it's also 'wandering'. So it has those two qualities which water has: it wanders, but it also pulls you, to the bottom. I think I'll end with a Novalis quote. It also relates to the night. He says: 'Zugemessen war dem Lichte seine Zeit, aber zeitlos und raumlos ist der Nacht Herrschaft.' 'Measured was the night's time, but timeless and spaceless is the night's reign.'

[Top]