Interview with Margarita Gluzberg, artist

Conducted by: Tom McCarthy (General Secretary, INS)

Venue: Office of Anti-Matter, Austrian Cultural Institute, London

Date: 03/04/01

Present: Tom McCarthy, Margarita Gluzberg, Anna Soucek, Corin Sworn, Anthony Auerbach, Others

Tom McCarthy: Your work is very relevant to the aims and interests of this organisation, although this might not seem self-evident at first glance. In fact, at first glance it's quite difficult to locate what it is that you're doing and the concerns your work has. For all its brutality - and in one sense it really is quite brutal - it's also very subtle, with a real tenderness to it. So I thought we could start by going back to its prehistory, and look at how it came about. You studied painting originally, didn't you?

Margarita Gluzberg: Yes, I studied at the Royal College of Art. But even then I mainly did photography. I did three paintings, then went straight to the dark room and stayed there for the next two years. So really I started out making photographs. And the reason that I then ended up doing what I'm doing now, which is drawing, is because photography was such a distant medium that I didn't have anything to do in the studio after a while. I was just outside wandering around taking pictures of the backs of people's heads.

TMcC: They're always turned away, aren't they?

MG: Yes, I did a whole series of the backs of heads, which was sort of about having nothing to do, and about aimless urban wandering. I got obsessed with this vision of the back of men's heads. It's quite an erotic zone, the neck - especially if they're businessmen with white collars and you're standing behind them. I used to take hundreds of photos like that - but that became a ghostly activity, because everything is mediated by the camera, and I as the artist didn't have anything to do.

TMcC: Didn't you develop them yourself?

MG: Yes, but that became a perfunctory task. And when I started making these wig drawings, which were enormous and detailed and absurdly monstrous, they were empty heads: this kind of space inside your head which you can't see, this deep hole which is the blackness of the inside of the head. I imagined that businessmen's heads would be deeply disturbed and weird inside, underneath all their hair. So then I started drawing the hair without the heads, and the deep holes of the heads.

TMcC: You really can see the deep hole. It's as though you'd drawn the wig-stand and then taken the stand away.

MG: Yes.

TMcC: There's something fascinating in a formal sense about these drawings. Most people, when they draw, imply the whole without actually 'doing' it; but you do exactly the opposite. When you see your drawings in the flesh, and specially from sideways on, you see that the graphite is actually emerging from the paper, because you do literally every single stroke. That's quite unusual.

MG: Yes. I'm not really interested in effect. I have an obsession with surface - but surface as matter. This becomes more obvious in the later drawings, which take themes from fashion. But even with the hair: the reason I started drawing hair is that I'm quite a formal artist, and also incredibly pedantic conceptually, in that there needed to be a conceptual reason for making a drawing. So every hair became a line, so that it was a direct translation of one dead thing - dead hair, a wig - into another dead thing, lead. Wigs are superficial things that cover your head but they're also sculptures made out of lines. So the drawing is a sculpture too. I'm not interested in illusion, basically. I'm interested in surface physiology, dead matter.

TMcC: At first you did a series of 'real' wigs, that look 'right'. But then they start to - you could almost say 'go wrong'. They start mutating. How did that come about?

MG: When I started making the wigs, which were nothing, units of hair, marks, lines, they started growing and mutating. I really did think of them as things that grow - dead things that grow; they became more and more monstrous. I was also thinking of a mathematical paradigm, which is ironic because maths was never my strong point. But the only thing I liked about maths was topology, where one thing can turn into another if you have a given set of vectors which can then be translated.

TMcC: Flows of surfaces…

MG: Exactly. I remember this old teacher saying you could turn a cup of tea into a Christmas tree, and we spent five lessons doing that. So I thought of the structure of the wigs as a malleable structure. It had a set number of hairs, but those hairs could make up any other surface if you configured them another way: mutate. One drawing I did was called 'Heart-shaped Wig', which is a wig that has the illusion of being an organ; so it no longer had a gap: it had a structure and a shape. So it was about turning holes inside out, turning the cavity that's the head into an organ that's the heart through a mutation of surface. They're actually quite funny too, in a macabre way. The heart actually came from a father Christmas catalogue. So it's ironic that something that's quite pathetic can be turned into an organ, a surface that means something else.

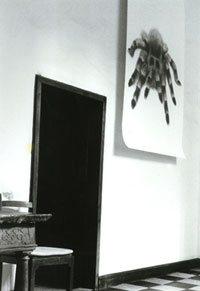

TMcC: They're quite disturbing as well. They start suggesting animals, but not cute, fluffy animals. They're really horrible: spiders and dogs - not cute dogs but disgusting little Chihuahuas, the type you want to kick whenever you see them. Why did you go to the monstrous, the grotesque end of the scale?

MG: I was thinking of failure. All this matter failing to become something meaningful, failure of matter to form into something that's formed successfully. I was reading a lot of Philip K. Dick at the time.

TMcC: There is something very sci-fi about them.

MG: Yes. My favourite Dick story is Three Stigmata of Palmo Eldrich, which is all about this artificial world full of death and ghosts, where things appear and disappear among ghosts of things past; it's set on a Martian colony where people are so bored they take drugs and play with these layout pads, these toys, that enable them to imagine themselves as glamorous people on Earth. And Dick has these ridiculous animals called Glucks. It kind of bites your leg, but you're not quite sure what it is, if it's real or artificial, a man-made or fictional construction. So it's sort of unformed matter that's scurrying around in a semi-humorous way snapping at people's ankles, and it's pathetic and ridiculous: monsters that fail to be monsters because their materiality isn't sufficiently formed to engage with our reality, so they hover, half on the other side, their lines not being generated into something substantial.

TMcC: We're getting into deep philosophical territory here. I start detecting a whole thesis that you could call Hegelian or Bataillean about matter and transcendence. The matter here is reject matter: stuff that didn't get what Hegel would call 'aufgehobt' - didn't get sublimated, rendered sublime; it just got twisted up and left behind. I know you read philosophy voraciously, and I wonder if it's instrumental in what you do, or does it come in after the fact and help you understand or articulate what you've already done?

MG: It comes more after the fact. I'm mainly reading novels now. The only philosophy I read at the moment is Deleuze, and that's because of his conception of matter and the immediacy of the material. In A Thousand Plateaus there's this notion of close-up space, haptic space, space that becomes as you read it. So these lines exist as lines as well as image: the lines are substantial in themselves. So when you look closely at that drawing of a spider, a certain type of space exists in the linear configuration as well as when they become an image. So image is matter, never metaphor. I'm not interested in metaphor; I'm interested in the actual. We can come later to the fashion stuff - but even something really superficial, surfaces, aren't metaphor, they are what they are. They exist as image, but as image-as-actuality.

TMcC: Another Deleuzian figure your work brings to my mind is his notion of the 'body without organs' - a misnomer because Deleuze actually means a huge proliferation of organs sprouting in all directions in the wrong places. Was that something you were thinking of?

MG: Not really. I always think body without organs is more of a political construct, like a country without a central mechanism…

TMcC: Deterritorialised.

MG: Yes. So what interests me there is that I've always been into the destruction of Renaissance perspective. It's very anti-Deleuzian, because it's long-distance vision: you stand at a fixed point and see the distance. The sprawling legs of my spider are the opposite: they're without perspective; they go in all directions. Spiders are creatures of fear, but I think one of the reasons we fear it is because we don't know which direction it'll go. Legs that can move all at the same time in many directions is something frightening to the western paradigm of society, because we're trained in that Judaeo-Christian world of perspective.

TMcC: But what about your butterfly? A butterfly is not just something that mutates; there's also this whole realm of mimesis going on - something that Nabokov hugely plays up in his work. In your one you've retained the markings, the maps.

MG: The markings: again we go back to this idea of surface, and vanity. Vanity is becoming something that interests me more and more. Camouflage and vanity. The butterfly, as I depict it, is a monstrous thing. Its markings are so elaborate and yet it dies so quickly. It seems to be all in vain. I'm making an image at the moment for an auction in a castle (I seem to keep doing stuff in castles), and it has to be based on an object in the castle, and I've noticed that in all the portraits of the family they're wearing this ermine fur, white ermine with black markings, this regal thing. I checked out what ermine are, and they turn out to be these really weird creatures that change to brown in the summer. So it's only in the winter months that they're white with black tails, which is the desirable state for hunters. They symbolise purity in Christian mythology, and according to legend hunters used to smear the entrance to their lair with mud because these ermine would rather die than be covered in mud. So these white things would sit outside and be killed by hunters rather than get dirty. So I always saw it not as an image of purity but of vanity: I'd rather be seen dead than in the wrong coat. And it goes back to surface and the wigs and what we expect from the outside. So ermines' very being, their essence, their character, is configured by their outward appearance and by their material appearance. Which goes back to Deleuzian notion of becoming: we are configured by the substance of which we're made, which is image, but also actuality and matter. People always want to treat the drawings as metaphor, but I see them as absolute construction of the real.

TMcC: I'm going to ask you about fashion in a minute. It's very important in your work. But first I want to talk about the erotic. The latest work of yours is called 'Feel it in Two Places'. It's a huge drawing.

MG: Yes, three metres by five metres.

TMcC: It's very violent and very erotic. There's something animalistic about it: in the animal kingdom sex is rapacious and very often linked to death - with spiders, for example, black widows. I wonder how important death is for you. I mean, it's the ground zero of all transformation.

MG: Well, this piece is metaphor, but material metaphor. Matter-meta, meta-matter. My meta-matter of choice here is these black spots that I use. I've made a series of hearts covered in them as well. They're basically these black spots you get in Hogarth. He uses them all the time. They're beauty spots, but they're also syphilis: syphilitic pockmarks would be covered up by these beauty spots. So these black marks camouflage. Balzac always talks about beauty spots as this mode of seduction; in Cousin Bette he has a whole chapter on the beauty spot. So it's sex and death - but they're also these black anti-matter things which are both death, the onslaught of decay, and the markings of beauty, like the black spots of the ermine. I like the idea of things looking the same over different configurations. One of the things Brett Easton Ellis keeps seeing in the characters in Glamorama, who are the characters of death, or at least ciphers of this parallel reality which he begins to inhabit, are these black shapeless tattoos. So as he's about to have sex with this woman on a ship, who becomes a terrorist as the book becomes a film and it all disintegrates into chaos and violence - as they're about to have sex, he touches her and sees this black, shapeless mark, this recurring tattoo. So I'm interested in this mark that's been put on the skin and becomes part of the body, a material sign. So I wanted this drawing to be a cross between - well, it's too presumptuous to say it so I won't…

TMcC: Were you going to say Georgia O'keefe?

MG: No, I was going to say Hans Bellmer meets Channel. It also has lots of Louis Vuitton flowers on it. It's a kind of masturbating drawing, I guess. Someone said it looks like a bonnet, but I don't know what kind of bonnet looks like that. The bonnet from hell.

TMcC: You should make it, and get someone to wear it at the races.

MG: Yeah, Royal Ascot Hat Day. But yes: the drawing's covered by these Hogarthian marks. I really like this idea that when society disintegrates for him everybody's covered with these beauty spots. So in that sense death is between that which we want and that which brings about our downfall.

TMcC: For me, Balzac in Le Père Goriot or Brett Easton Ellis in American Psycho have a more sophisticated take on death and society than Hogarth, because they don't see death as that which takes you away from society - it's absolutely central to your being able to function in the world. I like the fact that you've moved into fashion. Is that a recent thing?

MG: Yes, it is. I've done a big drawing recently called The Manolo Blahnik Creature, which is basically a Blahnik boot -

TMcC: What's Blahnik?

TMcC: It's an important shoe designer, you poor thing. It happens, conveniently for me, to be an animal print boot, with a stiletto heel, very beautifully made. I was interested in turning it into a kind of creature. For me, fashion is something that you can never get. It's a kind of monster - a desire-monster. So I make Channel logos that become creatures with their own autonomous existence. I think Madame Bovary is basically a novel about shopping. There's a fantastic scene where she's pursued by creditors and is about to top herself, and she runs to the fabric merchant who's one of her biggest creditors and is saying 'I don't know what to do!', this crazed woman who knows the end is coming. He says 'Yes, yes, whatever,' and shows her a bit of nice cloth - and in the middle of all this she buys it! In the very throes of death she buys more cloth! So she, as a reader, as the constructor of this romantic fiction which becomes her life, is actually made through material objects. And her death is brought about through her existence in the Unreal, in this parallel world constructed through things she can't afford. Her depression is set off by going to a ball and then coming back to this dull provincial town which is her life, and so she constructs this parallel world through buying Parisian magazines and knowing all about fashion and the interiors of rich people's homes - she basically reads Hello! all day long. So her downfall is brought about by this obsession with fashion - which, again, is surface, matter, the material world merging with the real world: it's the other side and it brings about death, and it's also the unreal life which takes place in the real life. It's a merging of realities that that sort of thing perpetuates.

TMcC: You've got into Jackie Collins recently…

MG: Yes, it's the same thing. They're quite violent books; everyone's always dead. She's a kind of repetitive version of Balzac and Brett Easton Ellis; she's like a conceptual artist because she writes the same novel over and over again, or like Morandi painting the same picture. Her world is the world of the dead - of materiality, decaying Hollywood. And she always talks about venereal disease, in this kind of Hogarthian way. The Jackie Collins world would be covered in black spots too. Signs becoming matter in relation to death. I'm much more into Catholicism than Protestantism, even though I'm born to half-Communist, half-Jewish parents. What interests me in Catholicism is that the metaphor becomes matter: you are actually eating the flesh of Christ and drinking his blood as you take the communion wafer and wine - it's not a metaphor, it's literal. I still salivate when I see the Channel sign; even on the way here I stopped off in Harrods and I was almost - well, it was exciting, let's leave it at that. So they're signs, but they're actual because they bring about a physical reaction. So my way of making monsters is to make a sign actual in the same way as Catholics eat the flesh of Christ actually, not metaphorically.

TMcC: Transubstantiation…

MG: Yes: I'm interested in language becoming transubstantiated into matter. Bringing metaphor into the actual - which is a kind of relationship with the dead. Death is so much to do with the problematics of describing something. One of the things I'm interested in is to describe, to translate. I've worked as a translator from Russian into English and vice versa. In my work I'm translating from notion to pencil mark, from sign to creature. Our problem with death is that we can't describe it, and I think that's why Catholics have got it sorted: they just have it for tea.

TMcC: Catholics Eat Death for Tea. It should be a bumper sticker. Hey: how was Elsinor Castle?

MG: Elsinor Castle was interesting. It's allegedly the castle that Shakespeare based Hamlet on. It's quite a modernist castle. When you and Mark Aerial Waller showed Edgar G. Ulmer's The Black Cat the other night I was reminded of Elsinor - it was restored in the twenties with an IKEA look of wooden floors and white walls. I showed in this biennale a series of black hearts; and I showed spiders - which live there too, so it was nice to find an appropriate home for them. I showed these pockmarked hearts in the officers' quarters, which was appropriate too because I imagine these officers having duels and killing each other, either with guns or with syphilis. I saw the hearts as maps of these officers' twisted souls. It was a bizarre experience: I had to deal with strange colonels who guarded the castle.

TMcC: You told me you had to row there…

MG: Well, I had to get a boat over from Sweden.

TMcC: I imagined you rowing to the castle each day, like Charon.

MG: I was staying in Sweden but going to Denmark every day. Crossing the water. With my obsession with fashion, I kept deciding I was wearing the wrong dress and whizzing back to Sweden to change. I've missed planes because I've been trying on skirts.

TMcC: I remember calling you on your mobile when you were in some airport and you didn't have time to talk to me because you were buying clothes.

MG: Yeah, the airline had lost my bags for three hours, and I told them I had an important meeting and was wearing jeans, so they gave me a hundred dollars with which I immediately bought Donna Karen lingerie.

TMcC: And one of those disgusting novelty spider-puppets you get in airport gift shops, I bet.

MG: Yes, travel, spiders, many directions, death, fashion: it's all there. For me, shops are quite Deleuzian in their haptic-ness: they prevent me from moving to a fixed point or destination - I just move spider-like, sideways and forwards and back again from window to window. Deleuze describes what Eskimos do with snow: they don't look at a fixed point; it becomes a broken perspective where you touch everything, where everything becomes immediate; there is no point to get to; it's a nomadic space. With me that happens in the high street.

TMcC: So with the town that Roman Vasseur and I are designing for you, Margaritaville, we should put in a fashion chain called Haptic. Haptictat.

MG: Put in a whole Haptic Mall.

TMcC: So what are you working on now?

MG: Apart from the ermine drawing, I'm starting to do some works on mirrors. I've become interested in the slidy surface of things. Again, Brett Easton Ellis has this recurring line: 'We'll slide down the surface of things'. I like the notion of things slipping out of your control. It goes back to vanity, and seeing yourself in the mirror, and The Picture of Dorian Gray. That story's about vanity, but it's also about transformation of matter on the other side: even though it's preserved in life, the matter becomes the image which is death. I'm interested in this transmutating matter that's on the surface, so I'm working on sandblasted mirrors.

TMcC: Sandblasted?

MG: They're worn down till they become matt and you can draw on them, although you can't really see the reflection. I'm working on those, and also on coloured glass. So it's all very shiny and slippery. And I'm doing a wall drawing for a show with Lolly Batty and Sarah Dubai. It's on the actual surface, the wall - not an image on paper but an actual surface, invading the space itself so the gap between the viewer and the thing becomes confusing. So I'm making a piece on this wall about vanity. And I'm doing a clothes thing. I became very interested in shopfront design and its narrative - which is tied in with desire and haptic space and the thing that's on the other side, that you can't have. I was looking at a lot of nineteen-fifties shopfronts from New York, some of them designed by Dali, extraordinary surrealist constructions.

TMcC: Like what?

MG: Like one of a woman with her head covered with floating clouds suspended. A lot of suspension. A kind of space that doesn't really exist, but created as an image in the shopfront to sell clothes. I'm interested in using that form, and I'm going to make some three-dimensional drawings based on it. I've even been given funds to go shopping from Chelsea Art School. I applied for funds for normal materials like photographic paper and for funds to buy designer clothes with, and they said 'You can only have the ones for the designer clothes.' So the works will have drawing and actual clothes, in 3-D. I'm trying to invade our space more, like Dorian Gray's portrait invades his space. The matter which isn't mutating on his face is mutating on the other side, the dark side. I want to make the dark side merge with the space of desire and beauty. I've always been obsessed with Dorian Gray. I want to be him. Controlling death. Beauty. Fashion. It's like Madame Bovary: creating fiction through objects. Dorian creates the fiction of his life through the transformation of the portrait.

TMcC: I wonder if, with the mirror and the butterfly, the Lacanian motif of the 'imago' is relevant: this ideal image of oneself that you can never actually be. The way the shop window works: you couldn't actually live the life of that woman with her head in the clouds, or even of the woman in Hello! So the real and the fantasy start rubbing against each other and contorting.

MG: Don't you think religion provided that to some extent already? I'd like to mention the notion of geography. With our notions of heaven and hell we used to be much more geographical. So the desirable, perfect place was a geographical location.

TMcC: But geography's imploded now.

MG: Exactly. So if we talk about necronautism and the INS: philosophically, we don't have that fixed geography of heaven being upstairs and hell being downstairs, and your life was a road to one or the other. Now that's collapsed. I'm very interested in the geographical shift. To some extent Dorian Gray is a geography: what's where.

TMcC: It's a Bachelardian geography: the attic of his house…

MG: And he keeps his head covered up, like my missing heads. He keeps his bad things on the other side, in the perspective of the portrait - in that sense it's very modern - but he can't keep it from infringing on his life. So he can't have a separate geography: geography's merged. Maybe the shop window is closer to the Christian geography - although it invades too. I don't know. I'm not entirely clear on my geographical position. But I think there's an entire subject of geography that has to be addressed by your society. It would certainly be helpful to my life.

TMcC: We've started lines of investigation into Swift. I'm going to ask Will Self more about that this afternoon.

Anthony Auerbach: I think one has to be wary of the distinction between Renaissance geography and modern or postmodern ones. Perspective is already being undone in Renaissance painting - breaking itself down from the inside. But here's my question: is the heart also a logo?

MG: Completely. I wear lots of hearts. I like the shape.

AA: But that love-heart is not like a real heart, is it? We call it a heart, but it's more like a cunt, or a yoni-symbol, than an anatomical heart.

MG: I think it's a shape, a surface. It's a logo which also refers to an actual thing, an organ that pumps blood the system. But in my work it's a surface on which these markings happen. So it becomes almost a pin-up target. It could slide down. And it's flat. It represents love but it's very superficial. I'm doing stuff straight onto walls now, so it can be there one day and gone tomorrow, almost incidental - and ungraspable. And also like writing: things that slip along a surface, signs and meanings.

Corin Sworn: You deal so much with fashion and opulence and desire that I was wondering where guilt fits in.

MG: It's difficult. I'm someone who feels guilty a lot, but that's at a personal level. In my work, guilt's not obviously there, but I suppose it could be the darkness, the black bits. They could be seen as guilty in that they're not happy pictures. But that would imply that they're wrong as opposed to right, and that's not something I'm interested in.

TMcC: But if you take guilt not as a psychological state but as an ontological one to do with matter: in Christian doctrine matter, the state in which we exist, is tainted.

MG: In that sense the black spots are tainted matter.

TMcC: Failure. In the philosophical tradition, which is also a pretty Christian tradition - say, in Hegel - matter is failure.

MG: It's failure because it cannot ever successfully describe. Whether it be the materiality of language - and I treat language as a kind of matter, I think - or the physical act of making an object, it's always a process of failure, failure of description.

TMcC: And the resolution of that failure into an art work. If you were a poet, you'd be Francis Ponge.

MG: But do you think there is always failure?

AA: It seems to work two ways. Simon Critchley was talking about Hegel, where identity is death and representation is death. You take the sign, and feed life into it, and kill things by describing them.

TMcC: But then poetry starts where Hegel starts failing.

MG: So do you think there is a failure always in describing, or not?

TMcC: Yes - but I'm glad there is. That's where the very possibility of poetry is.

MG: But that means the necronautical project will always fail.

TMcC: Absolutely.

MG: It's doomed. Completely. Because one will always fail to describe. You're faced with the greatest problem: not being able to describe that which is undescribable.

TMcC: That's what opens up the whole possibility of doing it. I can't go on, I must go on, bla-di-bla-di-bla: that's the sort of logic we're inhabiting.

MG: That's also the project of science, effectively. I've always been struck by the fact that that which was deemed to be supernatural, like hearing voices - well, in fact it's the telephone or the radio. For me, scientific development was always a project to describe the supernatural. Flying and all these dreams, all these things that people saw to be magic, become scientific. So everything that's currently deemed undescribable comes from the realm not of the magical but of the unknown, and the project of science is to describe it materially and actually. And maybe finding words for things is also a scientific project. And the necronautical project is a way of trying to describe something more and more.

TMcC: You get these watershed moments in science. Like Freud: in a way, he was the last rationalist. He was saying: 'We're going to colonise the unknown with knowledge, with reason, so that we can explain everything.' But at the same time he was coming from the other side. He was saying: 'Classical metaphysics has taught us that we are what we know, like Descartes and all that, but I'm saying that we are precisely what we don't know!' So at places like that it starts going both ways. And literature hovers around that sort of zone too, at which language and reason meet with their own being-confounded, their own trashing.

MG: They meet with their own trashing, but they develop their own selves as well, and get generated by their own meanings. So descriptions become the world. So drawing becomes an actuality, and the process of making work for me is to make it real. To put it always in the world of here, pull it out of the other side. So Van Gogh's sunset is the description of something becoming itself. So words, and the way we describe things, and the way that literature operates, for me, is that it makes up its own configurations and therefore it is what it is.

TMcC: It is what it is. But this is why I so love Blanchot and his whole working through of this question 'What is Literature?' What makes language literary as opposed to scientific or whatever? He comes back to these radical and irreducible moments of failure and of disaster. The 'event' is the centre of the whole thing, but the event is a catastrophe - one that's always already happened and yet is always yet to come. And in his take on Orpheus, Orpheus going into the underworld to retrieve Eurydice his wife doesn't want Eurydice so much as the face that will always be turned away, the night at the heart of the night. And he so he has to betray his task. The reason that he's such a great poet is not that he goes to the underworld, the other side, and brings something back, but rather that he goes and fails to do that. He fucks up. So Blanchot concludes: the work consists of the artist's failure to execute the task of the work.

MG: We mentioned the brutality of things in relation to my work earlier. Violence is something I've tried more and more to put into it; 'Feel it in Two Places' is quite a violent drawing, and this one I'm doing on the wall now is a kind of wrist-slashing drawing about vanity: the act of killing yourself as a vain act but also as something that constructs itself. So I wonder: how does violence play a role in this whole notion of 'the event'? Is the catastrophe the thing which describes or is the catastrophe the thing that fails itself?

TMcC: In Blanchot, violence and the catastrophe are not the same.

MG: So is catastrophe accidental?

TMcC: The catastrophe is just given. It's like time in Beckett, or in any tragedy: it's just there, and it's what you're in, you're in time. So you're in the space of the catastrophe. But the catastrophe's not the same as violence. Blanchot's reading of Sade is that violence is the passage between understanding and, you know, Dasein, what is to be understood. So the sadist, in killing - in modifying, he uses that word and not 'killing' - his victim, is communing with the truth. In Bataille you get that expanded into a whole system.

MG: And is that system built to escape the constructs of the capitalist space? A political act? Or to negotiate it at least?

TMcC: No. Bataille's not really revolutionary. He says: these moments of festival and intoxication, which would seem revolutionary because they're the exact opposite of the logic of the marketplace - so for example potlatch, which would seem like the contrary of the principles of exchange (you don't exchange stuff, you just destroy it), is according to Bataille at the heart of any system of exchange, in the same way as for Lacan the other is at the heart of the self - and these moments of festival, when all the rules are broken and you can go and have sex in the street or whatever, are actually instrumental in facilitating the smooth running of society and order.

MG: That sounds like an almost pornographic notion. By pornography I mean this sort of space where everything that's negotiated is completely unreal. It's this other thing which is just there and you watch it in hotel rooms when you're abroad or something, when everything's forgotten. So it's not transgression that I'm interested in in Bataille; it's more this kind of space, which is perhaps linked with slasher-movie violent space. I think that's true, even though I hate doing that; it's like saying 'Deleuze is like going to Thailand'.

TMcC: That's what Al Lingis says.

MG: Yeah, it's a cliché. But I'm asking all this because in 'Feel it in Two Places' I really want to make a pornographic drawing. I'm going to tell you something really bad about myself now. Children are quite sexual, and when I was about six or seven I used to entertain myself by drawing, because I grew up in communist Russia and we didn't have tv or nuffink. So I used to have piles of paper, and I'd draw myself stories. Now, I went through a pornographic phase - and all of them were about women being mutilated sexually. I was scratching really hard around their genital area. I probably need lots of therapy for this, but I don't actually think I do. I was doing this stuff and I was turning myself on. Now that's a classic Bataillean transgressive thing, but I've always been very interested in violence and pornography and how you bring these together, because it's also very much about how we deal with the physical. It goes back to matter and desire and how to describe something which is physical. Fashion is physical too. These things are all linked, and they all go through this kind of Blanchot non-space - and interestingly enough, the Surrealists talk about this space too, this strange space which we can't quite name or describe.

TMcC: The Surrealists are sort of 'good' boys. They were straight-up Hegelians, and he's a Christian theologian, with a very classical geography of transcendence. Breton says in the First Surrealist Manifesto: 'I believe there is a place where the perfect synthesis of dream and reality happens, and all matter gets elevated to the sublime and so on'. Now, Bataille and Blanchot signed the First Manifesto along with Jabes, Leiris, all these people, but then they all fall out around the time Breton decides they should all become communists. So they leave and become 'bad' boys. And they become much more interesting. And I think that's when we start heading towards the sort of space you're gesturing at. There's one line in Bataille, this brilliant line where he says it all comes down to matter, and matter can only be defined as 'the non-logical difference which represents in relation to the economy of the universe what crime represents in relation to the economy of the law'. Hegel's only interested in matter when it can get aufgehobt, killed and reproduced on this sublime plane: that's what wisdom is for Hegel. It's an act of violence. But Bataille's violence is an act of violence against that violence. It's saying: no - let it resolve itself violently and tortuously back as matter in the here and now, and as a type of matter that's born out of the failure of the programme Hegel's describing. It's a crime against that programme. And it's non-logical difference; it's just this lump which is there and ugly and grotesque.

MG: Yeah: it's actual but you can't access its reconfiguration of itself. It won't deliver itself. It's almost like turning a space into an object. So the negative space becomes a thing. That's close to Deleuze where space becomes itself, unfolds onto itself, transforms itself. It can't be shaped: it shapes itself as it moves through. I like that. My picture, my construction then makes absolute sense: it's a thing that should fill space but in fact it is space.

TMcC: Yes: that's a really good thing about your work.

AA: You talked about vanity in relation to fashion, and the strong thing about vanity seems to be self-love. But there's the other side to vanity, which is futility. Do you include that second sense when you say 'vanity'?

MG: Yes, I suppose so. But really it's vanity in relation to surface and vanity in relation to an act of violence, a meaningful act. I think vanity's quite violent, and that the act of violence is an act of vanity. So the violent contortion of that lump we've just described is also about trying to see yourself as a material thing in the world. So vanity probably is bad, because instead of being inside this matter thing, you try to see yourself as outside it, and therefore it's a failure, because you can't be outside of yourself. The vitrine, or Glamorama, or Thackeray's Vanity Fair: it's always about seeing yourself from the outside, as a character in a film. And that's always a doomed thing, because you can't be outside of yourself.

AA: So what about self love?

MG: Self love doesn't come into it.

CS: Maybe it's more about determining yourself through others' eyes. So the narcissistic self can't understand themselves in terms of their own identity but continually reshapes it through the group they're with.

TMcC: For the genealogy of vanity in art, we've got to go back to the Dutch, and all those Vanitas paintings. They're complex, because they were about matter, material possessions, and their through-line is: 'You may have all the goods in the world, but you're still going to die'. So it's about a relation of the self to possessions, and the market, and matter, and the skull - and they were commissioned by the wealthy guildsmen themselves, which is fascinating. They commissioned Vanitas paintings for them and of them, rather than nice paintings showing them playing real tennis or something.

AA: In that painting by Holbein, The Ambassadors, there's the skull which is undermining the prestige of the statesmen. But perhaps it's also showing the vanity of perspective itself. The anamorphosis makes the supposed fixed point of perspective unmoored. You go round to the point where you can see the skull from, but then the whole picture's gone wrong. But we forget that. We're so habituated to perspective that we can look at things from funny angles and still think they're 'right'. So it seems to me that Holbein's delving into the vanity of his own means of representation.

MG: I still think vanity is about seeing yourself. Dorian Gray's crime is his semi-success at seeing himself. That's the realm of the undead: the undead can see themselves, float above themselves, the classic out of body experience. It's the ultimate state of vanity. You can sort of see yourself in a mirror - unless you're a vampire, which is funny.

TMcC: There's feminists like Luce Irigaray, and her thing about the blind spot on the old dream of symmetry, and the speculum…

AA: You refer to the thing in Dorian Grey as a mirror, when in fact it's a painting. We're conflating the two. The mirror is also a perspective device. So all these things, picture and mirror and recognising the self as other, revolve around one another.

TMcC: Like a Gautier ring.

MG: Cartier! But I hate the word the 'other'. Sorry, but it doesn't mean anything. It's not 'other'; it's you. It's you or not you. Seeing yourself as somebody else isn't seeing yourself as somebody else: it's you as a double. I've always been obsessed with the double. One of the most interesting examples of matter being animated is the eighteenth-century tradition of marionettes. The marionette theatre was a way of reflecting the world, and all the dolls had genitalia and were made like little people, and they were meant to reflect the human being and its soul. So it's like Frankenstein, the double that mirrors you but is made out of artificial matter but is imbued with ourselves. It's matter that's fusing with this world and maybe some other world, but it's not otherness - it's merging.

TMcC: I think it's really interesting that you mention Frankenstein. That book, like so much Gothic fiction, comes out of the collapse of the metaphysical geographies you were describing earlier. There's this incredible bit in De Quincey when, pondering opium, he says: 'This is awful. Portable ecstasies can be carried in the pocket; Nirvana can be quantified and shipped down to London on the mail coach; the Divine can be measured out by the gramme and injected or taken as tincture or whatever.' It's about the commodification of the abstract, the fall of the abstract into matter. That's what the real horror of opium is for him. And with Frankenstein you get this collision of the Romantic, these Caspar David Friedrich landscapes when he's on the mountaintop in the Alps, this Romantic conception of the self, collapsing into an industrial one, meat-packing factories, yuk. But why did you just bring that up?

MG: Because I was thinking of Frankenstein's monster as a double for Dr. Frankenstein. But it's interesting that you mention the landscape; and it's about failure of matter again. There's this description of the monster, the creature (and I call my works 'creatures' because they're created) wandering round in his dispossessed state across fields, matter that's been rejected. And there's this other passage later in the novel where Dr. Frankenstein himself, after all his family's been destroyed by the monster and he's in pursuit of the monster, is described in his wretchedness as being like the monster, wandering through the fields and not sleeping and hating the notion of day because it reminds him of life, which he's lost effectively. So they merge into one being.

TMcC: And at the end of the book - the beginning and end, it's the same time - they're in that landscape of snow, of zero perspective, and they're described from the point of view of the people on the ship as two blurry black shapes which are indistinguishable.

MG: Black shapes again. So Glamorama is about the double, and so's Dorian Gray - there the two selves merge at the point of death. It's always at the point of death.

TMcC: Or the point of zero degrees. Frankenstein takes place at the North Pole; that's where the story is being written, on this ship. The scientist, the narrator, has gone there, as he says, 'to find the secret of the compass'. He wants to get to the absolute degree zero, the point of total truth, the ground zero of science. And what he finds there is the Frankenstein story instead.

MG: So does it mean that the fictional comes at ground zero of the real? Is it the real or the fictional that happens at ground zero?

TMcC: Maybe the fictional is the real of the real.

MG: The zero point is interesting. I've done a drawing called 'The Big Nothing', which is a big zero. It's in a book called Nothing. I've drawn a whole hairy zero, which is matter being zero, nothing - and it's from nothing that things stem. But maybe they don't: the zero could be the end, or the point of the meridian.

AA: Alpha and Omega.

TMcC: There's a Shakespeare sonnet about adding something to my purpose nothing, and that's how nature me of thee defeated. It's about these hermaphroditic contortions of the loved object, the one the poet wants.

MG: It's in La Jetée as well, when he returns to the point he came from, which is the fictional, although it's not.

TMcC: By returning to it the figure in his memory he saw dying on the jetty becomes himself and his own death. So he as a child was witnessing his own death as an adult.

MG: So it's the vanity of seeing yourself again, and death.

TMcC: In the Shakespeare sonnet the something and the nothing are genitals. 'Nothing' means the round hole of the vagina.

AA: The trajectory of these thoughts is producing a zero.

TMcC: So we've got nowhere.

MG: Yeah, let's go and have lunch.

[Top]